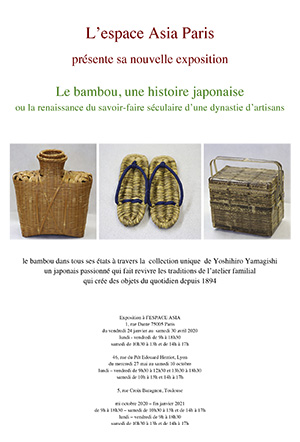

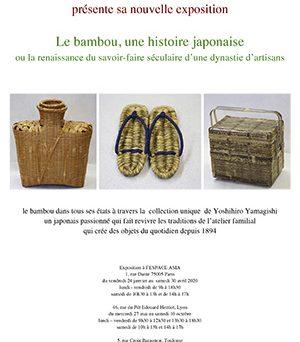

Le bambou,une histoire japonaise

ou la renaissance du savoir-faire séculaire d’une dynastie d’artisans

Espaces Asia et expositions

https://www.asia.fr/expositions-asia

■ Paris

du 24 janvier au 30 avril 2020

lundi - vendredi 10h-18h30,

samedi 10h-13h , 14h-17h

L’ESPACE ASIA

1, rue Dante 75005 Paris

■ Lyon

du 27 mai au 10 octobre 2020

lundi – vendredi 9h30-12h30 , 13h30-18h30

samedi 10h-13h , 14h-17h

L’ESPACE ASIA

46, rue du Pdt Edouard Herriot, Lyon

■ Toulouse

mi octobre 2020 – fin janvier 2021

lundi – vendredi 9h30-12h30 , 13h30-18h30

samedi 10h-13h , 14h-17h

L’ESPACE ASIA

5, rue Croix Baragnon, Toulouse

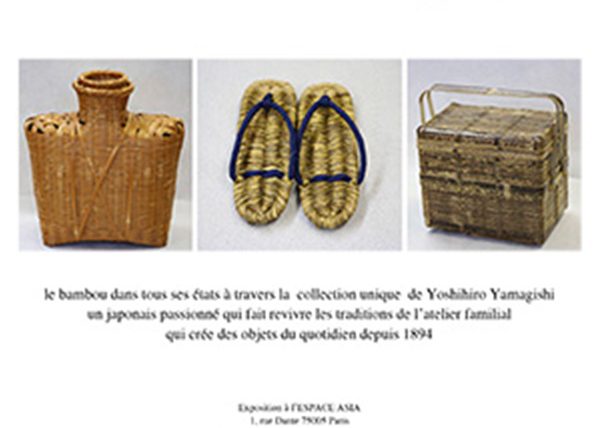

Le bambou dans tous ses états à travers la collection unique de Yoshihiro Yamagishi, un japonais passionné qui fait revivre les traditions de l’atelier familial qui crée des objets du quotidien depuis 1894.

All about bamboo – in a nutshell

Bamboo is a part of daily life in Japan

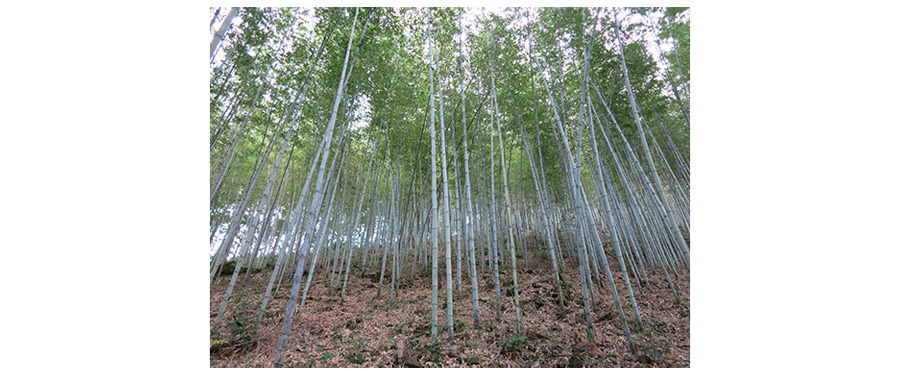

The first thing you notice when you arrive at Narita Airport and take the highway towards Tokyo are the countless bamboo forests you pass. You know immediately that you are in Japan – there is nothing like this in western landscapes.

Botanists have thus far discovered as many as 1 200 species of bamboo worldwide, all belonging to the same family as the rice plant and common grass. Their stalks are generally woody and hollow. About half of these species can be found in Japan, where bamboo forests account for approximately 1% of the country’s total forest area. This figure applies equally to the prevalence of bamboo forests around the globe.

The Japanese love bamboo, for its esthetic as well as its practical qualities. Quite clearly, the bamboo plant occupies an important place in their eveyday life.

Yoshihiro Yamagishi was born into a family that owns and manages bamboo forests and whose profession consists in working with bamboo. The family’s expertise reaches back four generations to his great-great-grandfather; in the tradition of Japanese artisan families, Yoshihiro Yamagishi is thus known as the fourth Taketora.

The family name Taketora in fact derives from a unique quality of the bamboo which the family cultivates and refines into various products. Take means bamboo and Tora means tiger, referring to the tiger-striped pattern that characterizes this species.

One feature of these special bamboos is that the canes only begin to reveal their tiger-striped pattern about three or four years after sprouting and, very often, only in the months following the first hoarfrost. Nowadays, owing to climate change, hoarfrost – and thus also the phenomenon of tiger-striped bamboo – is becoming rarer and rarer.

Further, not all the bamboo canes on the Taketora family’s plantation take on the tiger-striped pattern – only a part of them. The family therefore cannot simply harvest all the canes three or four years after their sprouting. They must know how to detect which canes will reveal the desired pattern. And this is not easy: there are no exterior features, indeed no sign whatsoever visible to the non-specialist, indicating the presence of the pattern. According to Yamagishi, only very experienced farmers are capable of knowing which bamboo canes will have the pattern. And this entails a generational problem, for the older farmers who possess this skill are dying out – many of them without having passed their knowledge on to younger farmers.

The celebrated botanist Tomitarô Makino (1862 – 1957), who founded the botanical gardens that bear his name today, tried to cultivate tiger-striped bamboos in his garden, but none of the transplanted colonies ever produced the desired pattern.

Our exhibition will help visitors discover a plethora of objects in bamboo which the Taketora family has devoted itself to crafting for four generations.

A short history of bamboo

Growth

Bamboo grows mainly in South-East Asia, East Asia, South America, and Africa, where the earth is rich in nitrogen, phosphoric acid, and postassium. The plant also requires large amounts of water to transport these three essential minerals through its vascular system. The best conditions for ensuring that a bamboo colony grows vigorously include abundant precipitation – at least 1 000 mm per year; a moderate average annual temperature of 10 degrees centigrade or higher; and plentiful exposure to sunlight.

To ensure the right conditions for bamboo growth, a colony should be planted at a latitude of not higher than 40° in the northern hemisphere, where average temperatures in the frigid months do not sink past 1 degree below zero. In the southern hemisphere, as in South America, Australia, or New Zealand, the latitudinal limit is the same – around 40°. In the Andes and the Himalayas, there are species of bamboo that grow at altitudes of up to 5000 m, but these are dwarf bamboos, called Sassa, which have evolved a better resistence to the cold.

New bamboo shoots springing from the colony’s underground rhizome system emerge once the temperature reaches at least 10° Centigrade – thus at about the same time as the flowering of the yamazakura (wild cherry tree), though a little later than the flowering of the famous cherry species called Yoshino. In the temperate zones, it takes between 50 to 90 days for a bamboo shoot to reach full growth. In the years that follow, neither the height nor the diameter of the individual bamboo cane changes. As a colony grows to maturity, however, its rhizomes will produce larger and larger shoots over the first few years.

In general, the life of a bamboo cane is deemed to commence once it emerges from the earth. The young bamboo shoot – called Takenoko – is a favorite dish of the Japanese when Spring arrives.

One may ask how it is that bamboo grows so rapidly. The reason lies in the internal structure of the plant: bamboo canes grow by virtue of a series of nodes which are activated one after another nearly at the same time. At the beginning, they are closed much like a folded paper lantern. As they open up one by one, the young bamboo culm grows until all of its internodes have fully expanded. A bamboo shoot has a large number of nodes – but this number never increases after the shoot has sprung from a rhizome.

Once the bamboo cane’s growth is complete, the nodes remain at the summit of the stalk or culm and each node sprouts branches and leaves. In trees, the sort of internal layer of bark called cambium contributes to the tree’s continued growth year after year. The bamboo plant has no cambium, neither in its culm nor in its branches, and for this reason it is usually not classified as a “true” tree.

Roots and flowering

Once the visible part of the bamboo has finished growing, its subterranean stems (rhizomes) have their turn. They begin to grow around the month of July and continue growing for about four months. During the summer, when there is abundant precipitation, growth accelerates, strengthening the colony and creating conditions favorable to the sprouting of new bamboo shoots. The shoots (takenoto) do not emerge from the earth, however, until the following Spring.The usual way to cultivate bamboo is to break off baby shoots from the rhizome as they emerge from the earth and transplant them. The flowering of bamboo forests is too unpredictable and sudden for the regular harvesting of seed.

Before withering and dying, the tips of bamboo branches produce flowers that resemble rice flowers. Bamboo flowers are difficult to see, for they are not showy and the stems and branches of a bamboo cane remain quite green right up to its death – which occurs shortly after flowering.

Everyday objects made from bamboo

In Japan, where bamboo forests are practically ubiquitous, the inhabitants of every region traditionally produced their own utensiles from bamboo. Whether professional artisans or simple farmers, they crafted bamboo objects at home when they could no longer work in the fields on account of the cold or snow – for the cold season begins just after the bamboo harvest. Nowadays, farmers rarely craft their tools from bamboo themselves, but the techniques for doing so have been passed down from earlier times to the present day.

The first major impetus for expanding the artisanal production of utensiles from bamboo came from the masters of the tea ceremony in the Muromachi era (from 1336 to 1573) under the reign of the Ashikaga shoguns and in the Azuchi-Momoyama era (from 1573 to 1603) under the reign of the Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The tea ceremony as created by Master Noami (1397 - 1471), referred to as the ceremony in the style of Higashiyama, was initially performed using utensiles imported from ancient China. It is the famous tea master Sen Rikyu (1523 – 1591) who introduced the use of simple, everyday utensiles, often crafted from bamboo – a tradition which has endured through the present day.

Nowadays, everyday objects crafted from bamboo include buckets and baskets for the transportation or presentation of fruits, boxes for carrying one’s lunch to work, and vessels for serving food, notably sobas, the tradition Japanese buckwheat noodles.

The Japanese also use bamboo to make racks for drying clothes, as well as umbrellas, fans, sieves for washing rice, chop-sticks, serving plates, and even sandals, brooms, spoons … They make eel traps, ladders, paint-brush handles, vases, and even musical instruments with it. And we should not omit to mention that the skin of bamboo shoots (takenoko) are used to wrap food with.

Finally, Japanese children love toys made from bamboo, such as stilts – Takeuma – and dragonflies – Taketombo.

To produce all these objects, the bamboo is never used directly after harvesting. First, it is de-greased by immersion in a boiling solution of caustic soda and then dried in a well-ventilated area shaded from excessive sunlight.

Bamboo in Japanese architecture

Bamboo has played a not insignificant role in architecture, too. Previously, it was used to make floorboards. And in mud-and-straw houses, bamboo stems served to reinforce the walls.

You will often see beautiful hedges of bamboo in temples and pavillions – both ancient and modern ones. As for example the hedges of the temples Ken-nin-ji, Ginkaku-ji (the Silver Pavillion) or Ryôan-ji in Kyoto.

To the Southwest of Kyoto, in the Chikurin (Rakusai Bamboo Park), a large number of different species of bamboo grow. Visitors to the park not only can see a large variety of bamboo species, they can also learn how the populations of different regions of Japan have traditionally integrated bamboo into their daily life.

Bamboo in modern life

Today, thanks to the progress of science, people have learned to use bamboo to make paper, textiles, products for the conservation of food, medications, and even charcoal. The quality of the charcoal and textiles made from bamboo is highly esteemed on account of the particularly fine grain of bamboo fibers.

Bamboo in traditional festivals and literature

Many popular festivals, tales, and proverbs in usage today make reference to bamboo. These include the festival of Tanabata, celebrating the stars Vega and Altair, and the tale of the princess Kaguya – Kaguya-himé.

The festival of Tanabata has its origins in an ancient Chinese legend about a daughter, Vega, born to the emperor of the heavens. An extraordinarily gifted artist, Vega wove fabric every day and married a renowned shepherd – Altair. But the princess and the shepherd were so in love with each other that they ultimately neglected their work, which angered the emperor of the heavens. He therefore separated them, compelling them to live henceforth on opposite banks of a great river – the milky way (amano-kawa). But the emperor was finally touched by their steadfast unhappiness and authorized them to visit each other once a year, on the 7th of July. The Japanese celebrate the love between Vega and Altair in the festival of Tanabata every year on this day.

In the evening, a magpie comes to rest on the river like a bridge and the two lovers meet on his back. The children are terribly sad if it rains that evening, for then the bird cannot repose on the river and the lovers’ tryst is postponed to the following year. But when the festival takes place as planned, children write wishes on strips of paper in five colors and decorate the branches of a bamboo culm with them.

The tale of the princess Kaguya was written during the Heian era (794 – 1185 A.D.) by an unknown author. Murasaki-shikibu, the author of the worldwide literary classic The Tale of Genji (written early in the eleventh century), said even then that the tale of Kaguya was the most ancient story written in Japan.

One day, an old bamboo wood-cutter finds an especially brilliant cane of bamboo. When he cuts it, he discovers in its interior a tiny little baby. Overjoyed at finding such a pretty girl, he and his wife raise the child, lavishing all their attention on her. Thereafter, whenever he cuts down a bamboo cane, he finds a nugget of gold. The little girl grows up, becoming more captivating every day. The news of her beauty spreads far and wide, and eventually five noblemen appear to request her hand in marriage. To elude their propositions, she promises to marry the one who can perform an inhuman feat. All fail in the attempt or try to trick her into acceptance. Eventually even the Emperor makes advances on Kaguya – but she refuses him, too. The old bamboo cutter and his wife notice that their daughter always appears sad when she sees the full moon. Indeed it turns out that the girl has come from the moon and is destined to return there. One evening, at full moon, a procession of bridesmaids descends from the Celestial Court to conduct Kaguya back to the Moon.

The story of Princess Kaguya is known to every child in Japan. It has been adapted for the cinema, in videos, and more recently in mangas.

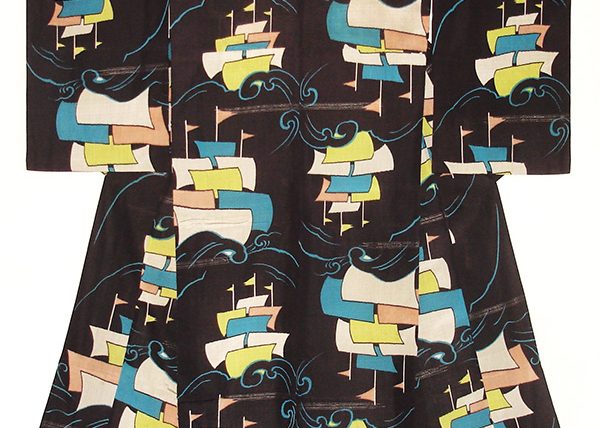

Japanese vocabulary, in which many different words are formed by the combination of two or more root words, includes many compounds employing the root sign for bamboo. There are also many folk sayings and metaphors that refer to bamboo. One popular expression, for example, is: « An upright man is like a split bamboo » . In sum, bamboo forms an integral part of Japanese esthetics. Whether in objects or on clothing – whether with reference to its beauty or to its practical qualities – everywhere you go you find the motif of bamboo.

Expositions Archives